Johanna Meyer-Grohbrügge

From ending up by accident in architectural studies, to eventually falling in love with the complexity of the field and the multitude of its layers, Johanna Meyer-Grohbrügge was amazed by the dual nature of architecture; its intellectual aspect, and physical outcome. Founder of Meyer-Grohbrügge in Berlin, the architect, and her studio seek to spatialize content, create relationships, and find solutions for living together.

After graduating from ETH Zurich, Johanna lived in Tokyo from 2005 to 2010. As explained by the architect, her time working at SANAA shaped her architectural approach “much more than her studies”, revealing “other ways of doing architecture” by questioning everything and the absence of preset rules; “You start as if you know nothing with every new project”. Appropriating this methodology of constant openness leads to the proliferation of options and eventually, conclusions. Seeing this as an intuitive way to approach a project, the architect understood the dichotomy between emotional decision-making – “what you feel is right”- and the pragmatic intellectual way of doing things as complementary. In her perception, there isn’t one right way, but she found herself more inclined to the specific sensitive SANAA method, which eventually convinced her to stay in Tokyo for 5 years to learn more about what the discipline has to offer. Basing her architectural approach on “reduction”; reduction of form, material, and resources, and on understanding the core of things, Johanna’s architecture creates relationships between the different components in action: people, building, context, etc. a leading principle in her projects which eventually serves as a complex tool.

Often described as "not your “typical” architect", Meyer-Grohbrügge explores different types of projects that are always centered around content. In 2010, she founded her office June14 Meyer-Grohbrügge & Chermayeff, and then Meyer-Grohbrügge in 2015, in Berlin. Having never lived in this city prior to setting up her studio there, Johanna perceived Berlin as a very open social center. “Everyone comes to Berlin”, she explains, “you don’t need to be a certain way to fit in this city.” Understanding that freedom helps her develop professionally, Johanna started with a couple of projects affiliated with the art scene, such as art galleries, art fairs, collections, and exhibition designs. Realizing that this world is open to things differently, she mostly got involved in projects where architecture is at the center stage and not just the background.

Having started young in academia, Johanna realized the opportunity of seeing things differently. Throughout her career, she has taught at several institutions, such as the Columbia GSAPP, the Northeastern University Boston, the Washington University St. Louis, and the DIA Dessau. Since 2021 she holds the role of Chair of Architecture and Spatial Design at TU Darmstadt. Knowing that her academic profession challenges her and allows her to look back at her projects in practice in a different way, the architect is trying to carve her own way, not wanting to follow the usual generic path of the field where you “build less and think more.” Today, Johanna is seeking to build bigger and have a larger impact, but constantly questioning “how to build in a good way”. Believing that this is the interrogation of the last decade, she acknowledges that nobody has reached a final solution yet.

Housing and work for Johanna are a priority in terms of the questions of the future, as both of these typologies will never disappear, and should be more integrated into our lives. Looking at the sustainability aspect, square meters, materials, and openness are key for the architect. In fact, she is supporting the creation of buildings that don’t have one singular program, but an open-frame construction that caters to the needs of living and working.

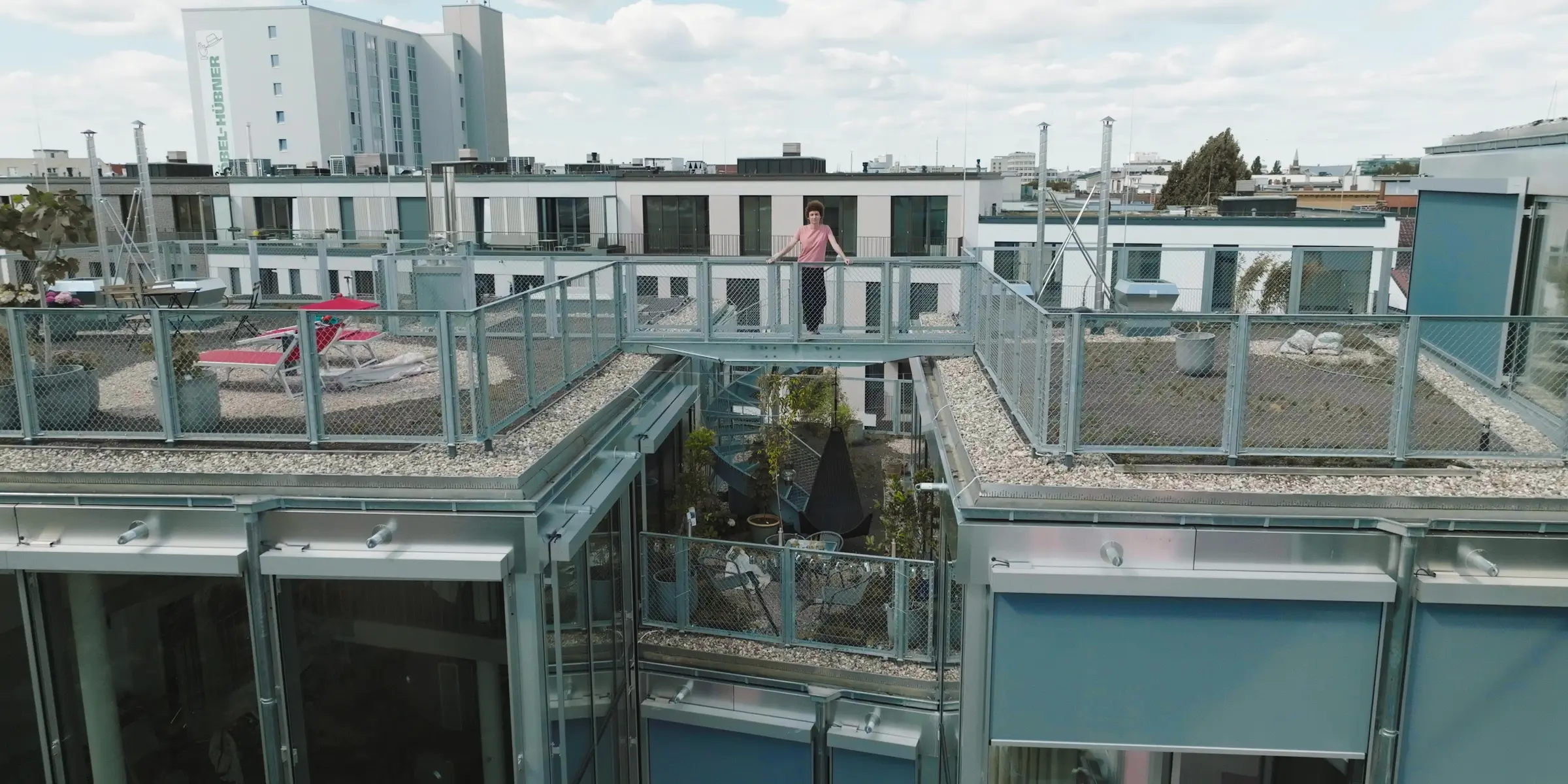

Johanna Meyer-Grohbrügge started her professional career with the KurfürstenStr. 142 project, a built residential building that is more about space rather than a prefixed function. Fostering privacy and communication, the structure creates a connection to the outside public plaza, while putting in place an intimate layer. Perceiving this as multiple floating intimate nests in the city, this intervention remains the studio’s breakthrough-built project. Through overlapping shapes, the structure mitigates borders, creating some sort of relationship with the neighbors, as well as certain privacy in an open space. In contrast with this project that took a long time to be developed, the Julia Stoschek Collection was designed and built in 3 months. A minimal remodeling intervention that was supposed to be temporary, the project consisted of a wrapping curtain that goes through the interior and exterior spaces to orient visitors and generates dark spaces for video art. Thinking about the office of the future, Johanna and her studio won a competition to design Volkshausgarten Leipzig, for the workers’ association ver.di. On-going, the project reflects on the synergies between landscape and architecture, bringing back, as is the case of all of Meyer-Grohbrügge’s projects, the question of connections. Other key projects in Johanna’s architectural career are the 11th edition of the Berlin Biennale and the Albanian pavilion at the Venice Art Biennale 2022, creating atmospheres and certain settings.

Not believing in one singular purpose, Johanna understands that “it’s much more important how you are doing something, rather than what you are doing”. Finding “simple spatial answers to complex questions”, the architect and her office Meyer-Grohbrügge seek to constantly establish relationships, between people but also between people and environment, and between architecture and environment.

Text: ArchDaily / Christele Harrouk

Photography: Boris Noir